Rikbaktsá

- Self-denomination

- Rikbaktsá

- Where they are How many

- MT 1600 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Rikbaktsá

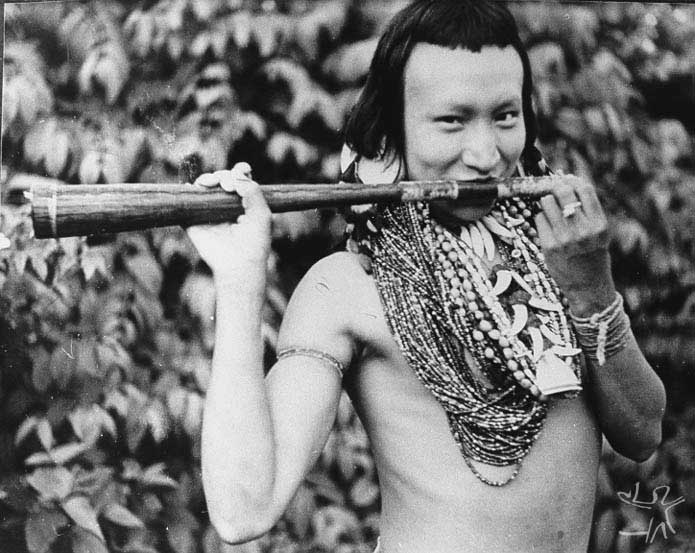

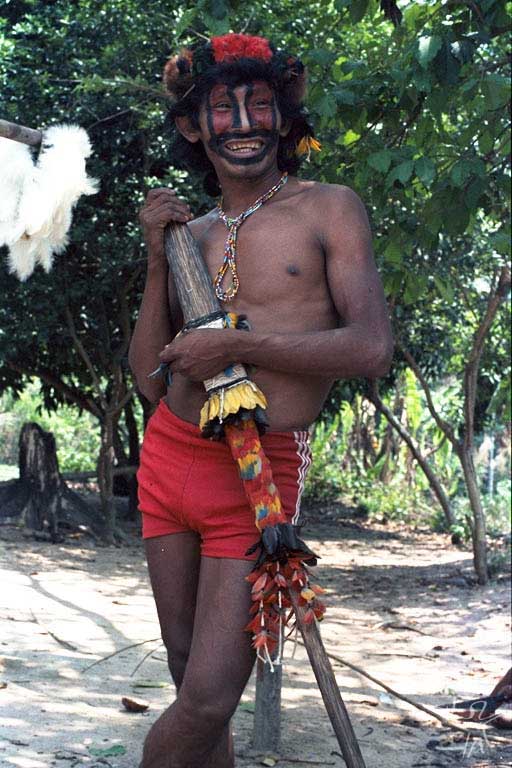

The Rikbaktsa, also known as "Orelhas de Pau" (Wooden Ears) or "Canoeiros" (Canoe People), reputed as ferocious warriors in the 1960s, experienced a process of depopulation that resulted in the extermination of 75% of their members. Now recovered, they still have the respect of the regional population in recognition for their persistence in the defense of their rights, territory and way of life.

Name

This group’s self-denomination – Rikbaktsa – means “the human beings”. Rik means person, human being; bak reinforces the meaning, and tsa is the suffix for the plural form. In the region they are called Canoeiros (Canoe People), in reference to their ability in the use of canoes, or, less commonly, Orelhas de Pau (Wooden Ears), due to their habit of using large plugs made of wood introduced in their enlarged earlobes.

Language

The Summer Linguistic Institute considers the Rikbaktsa tongue, Erikbaktsa, a language not classified in a family, but part of the Macro-Jê linguistic branch.

One of the interesting aspects of Erikbaktsa is the fact, common in many other Indian tongues, that there is a difference between the male and the female speeches, in such a way that the ending of several words indicate the gender of the person who is speaking. The knowledge and the mastering in the use of the language is recognized as more developed among the older people, whose conversations are usually followed with much interest by those who want to refine their knowledge of it.

Today the Rikbaktsa are bi-lingual, since they have learned and incorporated the Portuguese language. The new generations speak Portuguese more regularly and better than the older ones; they learn and use Erikbaktsa as they grow up and become part of the adult world. The older ones, on the other hand, have trouble using Portuguese and use it only in contacts with “whites”.

Location and history of contact

The Rikbaktsa live on the Juruena River basin, in the Northwest of the State of Mato Grosso, in two contiguous Indigenous Lands: Erikbaktsa, demarcated in 1968 (with 79,935 hectares, recognized and registered), and Japuíra, demarcated in 1986 (with 152,509 hectares, recognized and registered as well), and in a third Indigenous Land, do Escondido, demarcated in 1998 (with 168,938 hectares, it has been recognized but as of yet not registered), to the North, on the left bank of the Juruena, totaling a surface of 401,382 hectares of Amazon forest.

Their traditional territory is located between 9° and 12° South and 57° and 59° W, spreading through the Juruena River basin from the Papagaio River in the South to the vicinity of the Augusto Falls, on the upper Tapajós River, to the North. To the West, it reached the Aripuanã River, and to the East the Arinos River, near the Peixes River, encompassing an area of some 50,000 square kilometers.

Although isolated, the region has been visited by scientific, commercial and strategic expeditions since the 17th Century. However, little was known about the forest inhabited by the Rikbaktsa because, in the stretches of the Juruena and Arinos rivers that were part of their territory, the expeditions remained on the waterways or in their vicinity, almost never moving away from them. For that reason, until the arrival of rubber gatherers in the end of the 1940s, no mention was made of the Rikbaktsa. The absence of previous historical references and the lack of archaeological studies prevent the dating of their occupation of the territory. However, the tribal memory, the geographic references expressed in their myths and the extensive and detailed knowledge of the fauna and flora they show regarding their territory and its surroundings suggest that they have been there for a long time.

The Rikbaktsa were well known by the neighboring indigenous groups, with which, almost with no exception, they have maintained hostile relations. Famous for their warring ethos, they waged war against the Cinta-Larga and Suruí to the West, on the Aripuanã River basin; the Kayabi to the East and the Tapayuna to the Southeast, on the Arinos River; the Irantxe, Pareci, Nambiquara and Enauenê-Nauê to the South, on the Papagaio River and on the headwaters of the Juruena River; and the Munduruku and Apiaká to the North, on the lower Tapajós River. They resisted the presence of rubber gatherers until 1962.

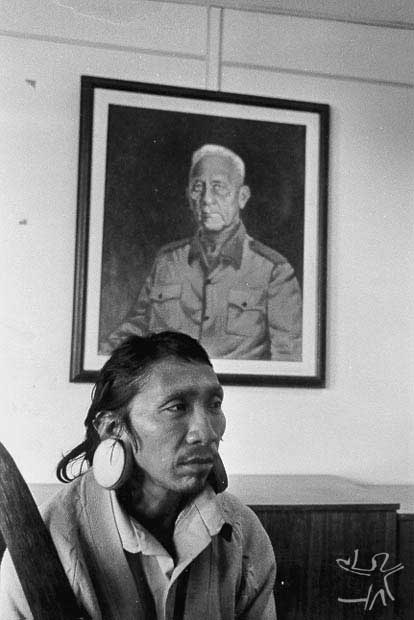

Since the “pacification” of the Rikbaktsa, which was financed by rubber planters and carried out by Jesuit missionaries between 1957 and 1962, their traditional territory has been the object of many pioneer fronts, such as rubber extraction, timber and mining companies and agricultural and cattle-raising enterprises. During the “pacification” process and soon after it, influenza, chickenpox and smallpox epidemics decimated 75 percent of a population, which was estimated in some 1,300 people at the time of contact. As a consequence, the Rikbaktsa lost most of their lands, and the majority of their small children were taken from the villages to be raised at the Utiariti Jesuit Boarding School (Internato Jesuítico de Utiariti), on the Papagaio River, almost 200 kilometers from their homeland. There, the little Rikbaktsa were raised along with children of other indigenous groups also contacted by the missionaries. The surviving adults were gradually transferred from their original villages to larger ones, which were centralized under the Jesuit’s catechist administration. In 1968, about 10 percent of the Rikbaktsa’s original territory were demarcated as the Erikbaktsa Indigenous Land; from then on their children began to be taken back to their villages, and missionary action concentrated in that area.

In the 1970s there was a change in the philosophy of the missionaries towards the Indians. They reduced their authoritarian posture, recognizing the right of the indigenous peoples to their own culture, thus opening the way for a more effective autonomy, which the Rikbaktsa had always demanded. Since the end of the 1970s the Rikbaktsa have struggled to regain control over part of their traditional lands. In 1985 they managed to recover the area known as Japuíra, and continued their effort to get back the Escondido region, which was finally demarcated in 1998. However, it is still occupied by miners, timber companies and colonization companies.

Population

The present Rikbaktsa population is a little more than 900 individuals. An estimate based on the size and the number of villages counted by the Jesuit missions sent to “pacify” them indicated a population of some 1,300 in the end of the 1950s. Diseases brought by the initial contacts reduced that number significantly.

Between the time of the first contacts and 1969, the number of Rikbaktsa was reduced by 75%. In the 1970s, however, there was a slight recovery, attributed to the protective intermediation of the Missão Anchieta (MIA). This mission, while exerting strong pressure towards the acculturation of the Rikbaktsa, at the same time provided them with the minimum conditions for the recovery of their population following the high post-contact mortality.

In 1985, according to a survey by the Jesuit Mission, the Rikbaktsa population had risen to 511 people, of which 153 had been born before contact and 357 after it. As soon as the epidemics were controlled and food production went back to normal, the Rikbaktsa continued to grow at a very fast pace, as the table below shows:

| Year | Population | % | Source |

| 1957 | 1300 | ----- | personal est. |

| 1969 | 300 | - 77% | MIA/SIL |

| 1979 | 380 | +26% | MIA/HAHN |

| 1984 | 466 | +22.6% | MIA |

| 1985 | 511 | +9.65% | MIA |

| 1986 | 514 | +0.58% | MIA |

| 1987 | 520 | +1.16% | MIA |

| 1989 | 573 | +10.19% | MIA |

| 1993 | 700 | +22.16% | MIA |

| 1995 | 905 | +29.29% | MIA/ASIRIK |

| 1997 | 950 | +4.97% | MIA/ASIRIK |

| 1998 | 1025 | +7.89% | ASIRIK |

The drop in growth rates between 1985 and 1987 seems to be due to a combination of higher mortality rates and low birth rates. This may be attributed, at least in part, to the turbulent period of struggle for the recognition of the Japuíra as an indigenous area, when food production diminished and health services became inadequate.

After 1987, when they already had the possession over the Japuíra guaranteed, as well as access to more resources and could hope for a more promising future – and, last but not least, both the MIA and the Funai (the official organ for the Indians in Brazil) were concerned more concretely with the health services in the area –, the Rikbaktsa population resumed its trend towards high growth rates.

Tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases, as well as deaths caused by malaria, continue to occur. However, since these illnesses seem to be relatively under control, it is possible to expect the maintenance of those high population growth rates in the future.

Economic activities

Natural resources are the Rikbaktsa’s main asset. The ancestral knowledge that they have acquired and have been transmitting orally to the following generations regarding plant and animal species, their interrelations and reproductive cycles, as well as the adequate use they make of them, have always ensured the Rikbaktsa’s biological and social reproduction. The sharing of such knowledge and the free and universal access of all members to the resources in their territory is responsible for the high degree of internal egalitarianism. There is no need to accumulate surplus, since the resources are “stocked up” in the forest and everyone knows how to retrieve them when it is needed.

Labor division is basically between men and women. The economic and political autonomy of the domestic groups, constituted as production and consumption units, is counterbalanced by the system of kinship relations (socially created) and of the ritual kind. Such system of reciprocal relations is the link with the larger community, the entire Rikbaktsa people. A break in reciprocity, which happens occasionally, is the cause of conflicts and differentiates the ties that exist between the various Rikbaktsa subgroups.

The Rikbaktsa see themselves much more as hunters and gatherers than as farmers, even though agriculture – and the ritual ceremonies associated with it – plays a central role in their social life’s pace and organization.

Rikbaktsa economy is characterized by the alternance along the year of different activities, which depend on the season. The production and consumption unit is the extended family, that is, the inhabitants of each residence. It is only during the rituals that take place with agricultural activities (clearing of new planting fields and harvest of new maize) and in a few other occasions that cooperation is wider.

The Rikbaktsa use slash-and burn (called coivara) to clear their round roças (planting fields), which have between half and 2 hectares. New roças are cleared every 2 or 3 years; the old ones are left fallow and eventually are taken over by the forest. Sometimes, in addition to the fields near the village, the Rikbaktsa have others, more or less distant, which, along with the abandoned roças, make up a source of food reserve from which they harvest roots and bananas, which continue to produce for years.

The Rikbaktsa plant two kinds of maize, different types of yams, cassava, rice, beans, cotton, urucu (the fruit of the annatto tree), several varieties of bananas, sugarcane, peanuts and pumpkin. They also plant pineapple, citrus (limes, oranges, tangerines), mangoes and other fruits, although not regularly. It is said that they used to plant tobacco for medicinal use.

The roças belong to the domestic group, which is comprised of the “owner of the ‘maloca’” (hut), his wife, his single sons, his daughters (both single and married), his sons-in-law and his grandchildren. The married man with children who move away from his father-in-law’s maloca and builds his own hut clears a new roça for his family. In most villages, however, the most enterprising and influential heads of family may clear their fields with the help of relatives and members of their villages and of neighboring villages, while at the same time sponsoring the ritual cycle of celebrations that takes place along with the annual cycle of agricultural activities.

New fields are cleared in May and June, when the dry season is well underway. In the capoeiras (open fields), clearing takes places from July until mid-August. Felled trees are burned in August/September; roças are planted after the first rains begin, in early October.

Much of the food eaten is obtained through hunting, fishing and gathering, activities the Rikbaktsa carry out all year long. Hunting is a male activity par excellence. The social role of the hunter/warrior seems to be the central point of reference of the set of values that constitute male identity, the “archetypical” figure of the provider of nourishment and defender of the community.

The Rikbaktsa eat almost every animal available to them; the few exceptions are alligators, anteaters, snakes, jaguars and the white-haired ape they “night monkey”. But they appreciate the meat of all other monkeys, which are their most frequent prey. Peccary is also highly valued, as well as agouti, pacas, deer (both red and grey), coatis, tapir (which they sometimes raise for food), various kinds of armadillos (of the giant armadillo’s tail cartilage the Rikbaktsa make bracelets worn by girls and women), river otter, tayra etc. Large quantities of various birds – whose meat and feathers are highly appreciated – are hunted as well: macaws, parrots, hawks, curassows, toucans, storks, ducks, cormorants, trumpeters, guans, tinamous, pigeons, owls and small birds of every kind.

The Rikbaktsa also eat all kinds of fish, as well as tucunaré eggs deposited in submerged tree branches, and river turtles and their eggs, which are found in large amounts buried to hatch in the sands of the beaches that are formed along the rivers during the dry season. Children as young as 3-years old can be seen playing on the villages’ ports killing fish with their bows and three-tipped arrows. They also catch newborn fish with their hands under the vegetation along the riverbanks and eat them raw. Although varied and practiced throughout the year, fishing is not always abundant. In the rainy season it becomes less frequent – the best time for fishing is the dry season.

In the rainy season, the rivers flood large parts of the forest, since the region is generally flat, with just a few hills. Many lagoons are formed then, and the fish, which have laid eggs in the end of the dry season, spread around the flooded areas, rich in nutrients. Their dispersion makes fishing more difficult, but the Rikbaktsa continue to fish, using mostly with bows and arrows.

In general, the Rikbaktsa are constantly aware of what nature offers them, directing their diet, their activities and their rituals in accordance to the rhythm of growth, alternance and maturation of the vegetal and animal life forms, natural resources which they take advantage of intensively at the appropriate time of the year. Gathering in the forest is a daily activity, and is practiced by men, women and children alike each time they leave the village; they take fiber to make rope and look for firewood, straw, wood for various uses, medicinal plants etc.

In addition to the extensive variety of wild fruits, the most important foodstuff in the Rikbaktsa’s diet gathered in the forest continues to be brazil nut. With high nutritive qualities, it is widely consumed, be it raw, ground, cooked and prepared as porridge, or as an ingredient for bread, cake or beiju (a kind of fried pancake made of manioc meal) dough, in addition to its use as oil for frying.

Also widely consumed is honey produced by various types of bees. It is used as a sweetener, mixed with water or in the several kinds of chicha, the generic name given to different varieties of soups and beverages that the region’s indigenous peoples prepare. The Rikbaktsa make chicha from bananas, soft corn, yams, corn with banana, local fruits such as patauá, inajá, buriti, buritirana, assari, seriva, bacuri, bamy, aboho, bamy with corn and an infinity of others. They do not make any kind of chicha – or, in fact, any beverage – that is fermented for more than two or three days at the most, and thus their drinks have no detectable alcohol content. Their chichas are tasty, very nutritious, and, in the hot local climate, prevent dehydration, and are consumed abundantly by all – men, women and children.

The Rikbaktsa prefer honey as opposed to sugar, even though the latter is widely used as well – raw, which they produce in small amounts, and refined, which they buy. Honey produced by the jati bee (a tiny, black and yellow stingless bee), which is fine, clear and has a delicate flavor, is considered ideal for children, and is believed to have medicinal qualities against coughing.

The Rikbaktsa raise several kinds of birds, thus having a living stock of feathers from which to make their ornaments, and to which they resort to every time they need. They raise macaws, parakeets, curassows, guans etc. The most common are the macaws (yellow, red or big-headed). It is common to see macaws walking around the houses, inside them or on trees near them. The Rikbaktsa show great affection towards them, and constantly feed them with brazil nuts, corn and other products. Despite that affection, every now and then the macaw, with feet and head firmly held and making a lot of noise, has its feathers picked and is left almost featherless. But in just one week the feathers start to grow again, with even brighter colors – more “mature”, as the Indians say. Many Rikbaktsa raise chickens as well, not only for their eggs and meat but also for the cock’s long tail feathers, which have been incorporated to the traditional feather ornaments and produce beautiful aesthetic effect. Last but not least, almost every maloca has a dog, a valuable help during hunting expeditions.

On the other hand, the Rikbaktsa have incorporated many products and utensils from the surrounding society, with which they maintain commercial relations, obtaining income, in the past few years, through the production and commercialization of natural rubber, brazil nuts and crafts (their feathery art is considered one of the most beautiful among Brazilian Indian tribes). From the agricultural and extractive production directed towards the external market that the Jesuit missionaries encouraged in the first two decades after the contact, they moved on to the self-organization of the production and commercialization of natural rubber in the 1980s, through an internal cooperative, organized in consonance with their social life.

In the last decades the deforestation of the areas around the Rikbaktsa lands have jeopardized the reproduction of wild animals, while the development of commercial fishing in the rivers that make up the limits of their territory has reduced fishing stocks, affecting both the activities of hunting and fishing and thus increasing their dependence on the outside market. With natural rubber prices falling down, especially in the 1990s, the Rikbaktsa have increasingly relied on the production and sale of feathery art, and, secondarily, in the sporadic sale of fish, brazil nuts and other products to the local small commerce as a way to obtain some kind of income.

As an economic alternative to the model of regional occupation based on extensive deforestation, the Rikbaktsa have been developing since 1998 a project of sustainable stewardship of their lands, based initially on the extraction and canning of hearts of palm for sale and, in the future, on the processing and commercialization of brazil nuts and other products. It is a pioneering initiative, administered by the Associação Indígena Rikbaktsa – Rikbaktsa Indigenous Association – (Asirik), created in 1995, with technical assistance of the Instituto de Estudos Ambientais (IPA) and the Instituto de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Humano e do Meio Ambiente (Trópicos), in partnership with Funai, the Coordenadoria de Assuntos Indígenas do Mato Grosso (CAIEMT), the Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e Recursos Renováveis (Ibama) and the city government of Juína, in the State of Mato Grosso, financed by the Prodeagro’s Programa de Apoio Direto às Iniciativas Comunitárias (PADIC) and the Programa de Gestão Ambiental Integrada - PGAI/PPG7.

Such activities directed towards the market are mixed – and sometimes are subordinated to – with the traditional economic activities, in a social project that is aimed at multiplying the income and the productive capacity of the Rikbaktsa while encouraging the preservation of the organization, rhythm and diversity of their daily life.

Social organization

Traditional villages used to be comprised of one or two houses, inhabited by extended families (the house owner and his wife, their single children and their married daughters with their husbands and children), and a men’s house (rodeio, in Portuguese; makyry in Erikbaktsa), where the widowers and the young single men used to live. In 1957, the missionaries found 42 of such villages; they were scattered around the Rikbaktsa territory, built in the forest in areas near the headwaters of streams, and were connected with each other by trails. With the centralization imposed by the Jesuits, villages became fewer and larger and tended to be built along the right bank of the Juruena River. In the past two decades, the recovery of parts of their territory (the Japuíra and the Escondido Indigenous Lands) resulted in the multiplication of the number of villages in the traditional style, even though some of them now have more than ten houses.

The villages have no definite format such as those of other peoples of the same linguistic branch, as is the case of the Jê family, who build circular villages that are a reflection of their social organization. Currently there are some 33 villages in the Rikbaktsa’s contiguous areas (the Erikbaktsa and Japuíra Indigenous Lands), located along the Juruena, Sangue and Arinos rivers, which form the limits of their territory – it is a strategy for keeping guard on their lands and for maximizing the use of their natural resources. In 1998, a new village was built in the recently demarcated Escondido Indigenous Land, where they plan to build others in order to ensure its occupation.

The Rikbaktsa divide the beings of the universe in two series, opposed but also complementary to each other. Such division, although used for other beings as well, operates more extensively in the Rikbaktsa society and, configured in the kinship system, provides the most encompassing classifying principle through which they organize their social life. The Rikbaktsa society is divided in exogamous Halves, one associated with the yellow macaw (Makwaratsa) and the other to the big-headed macaw – in reality, a variety of the red macaw – (Hazobtisa), each one of them subdivided into various clans, which in turn are associated with animals and plants.

<col width="25"/> <col width="205"/> <col width="195"/>

|

HALVES |

||

|

CLANS |

Makwaraktsa (yellow macaw) |

Hazobiktsa (big-headed macaw) |

|

- Makwaraktsa (yellow macaw) |

- Hazobiktsa (big-headed macaw) |

|

|

- Tsikbaktsa (red macaw) |

- Umahatsaktsa (fig tree) |

|

|

- Bitsitsiyktsa (wild fruit) |

- Tsuãratsa (little macuco bird) |

|

|

- Mubaiknytsitsa (spider monkey, coati) |

- Tsawaratsa (inajá, a type of palm tree) |

|

|

- Zoktsa (pau torcido, a type of tree) |

- Bitsiktsa (toucan) |

|

|

- Zuruktsa (a mythical, ferocious animal, a relative of the jaguar that no longer exists) |

- Buroktsa (pau leiteiro, a type of tree) |

|

|

- Wohorektsa (a type of tree) |

- Zerohopyrytsa (jenipap) |

|

Marriages are between persons of different Halves. In the 1970s there were marriages between members of the same Half – even though they are usually considered incestuous –, in part due to the high mortality post-contact, in part because these unions were encouraged by the Jesuits in their efforts to “civilize” the Rikbaktsa. Currently the traditional precepts are rigorously followed. Lineages are patrilineal, based on the belief that a child is generated by the father and always looks like him and never like his/her mother. In addition, the Rikbaktsa seem to believe that any man who copulates with a pregnant woman participates in the paternity. They say that the son takes his father’s place, is his continuation. The ties between father and child go beyond the moment of generation, and are considered a vital link (even more so than social ties) that is maintained all life long. The preferred marriage is between crossed cousins, and the rule of residence is uxorilocal, that is, the groom moves into his in-law’s house. The general norm is monogamy, but poliginy is allowed and occasionally practiced. Wedding ceremonies are very simple. Once the agreement between the families of the couple – and between the bride and the groom – is made, the village leader removes the groom’s hammock from his house (or from the men’s house) and ties it next to the bride’s, on her father’s house. The couple lives in the wife’s father’s house during the next few years, and moves away only after the family has become larger – then the family moves close to the husband’s married brothers’ houses. Divorce is common, especially during the first years of marriage, and is easily obtained by any of the partners.

Along with the relations of alliance among the patrilineal groups created through marriage, the classification principles of kinship determine the distribution of the individuals in the villages and establish relations of prestige and influence, being the heart of the Rikbaktsa’s internal political relationships. Relations between individuals, based on those principles, are classified through a system made up of more than sixty names, most of them forming reciprocal pairs.

The position a person occupies in the Rikbaktsa society is defined by the age group, sex, clan and Half. Gender places him/her in either side of the labor division and defines the chores he/she will perform along his/her life. This trajectory – and the social roles that will be assumed in it – is made along with other persons of the same sex and age group, who undergo together the same rituals that mark their entry into adult life. His/her belonging to a clan of a determined kinship Half, on the other hand, defines his/her marriage possibilities, his/her role and his/her obligations in the collective ritual celebrations, which are organized on the basis of the reciprocity of rights and obligations that each Half has via-a-vis the other. On the other hand, as they grow older, people are entitled to assume increasingly central positions in the organization of social life, until old age comes and place them in the highest level of respectability.

Children follow their parents in their chores since early age, helping them in their tasks. They learn to know the forest, its resources and its secrets through shared experiences and the teachings transmitted while performing their chores, as well as through the myths told to them by older people. Of the traditional rituals of passage, the Rikbaktsa practice the perforation of the boy’s ears and nose, in the end of the great final celebration of the ritual cycle that accompanies the clearing of the roças. Formerly they used to tattoo the girls’ faces and the boys’ chests during the ritual of passage into adulthood, which was followed by a ceremonial reclusion that could last more than one month, a period in which they should not take any sun, nor should be seen by any close relative. The reclusions, tattoos and the use of plugs in the boys’ earlobes have been gradually abandoned since the contact. Before it, at the age of 12 the boys would move into the men’s house, where a tutor would complete their education. Today boys live with their parents until they get married, when they move to their father-in-law’s house, and it is he who usually completes the son-in-law’s traditional education.

Each clan has a fixed stock of names, established in an immemorial past, which were used by all past generations and are continuously used by the living ones. There are children names and adult names. Along his/her life, a person may have three or four names; each time it changes, the former name is apt to be given to someone else.

The members of the father’s clan suggest the names, but the final decision regarding its adequacy belongs to the old men, not all of them of the same clan (but everyone of the same age group). They meet before the ceremony that takes place along with the clearing of the roças for planting and decide who is going to get a new name (both children and adults) and which one it shall be. During the ceremony, in the evening chant, the “owner of the ceremony” announces the names and the individuals who got them.

A child may get the “child name” that his father, grandfather or older brother has already used. Even though it is more common be given names whose last users have died at a very old age after a full life, a man can get a name that has already been used by his father, grandfather or another clan member even if he is still alive.

Except in the case of small children, no one is called by his/her real name. The Rikbaktsa call each other by kinship terms, Christian names, nicknames or referring to a known relationship established by a third person.

A person’s real name is known only by close relatives and allies – those who take part in the same ceremony of clearing fields – and is usually unknown to people with whom the person maintains distant relations. For enemies it is a secret. But even those who do know the name do not say it in public – to expose someone’s name in such a way is considered rude, an invasion of privacy. The name of a person who is not present cannot be mentioned either. Only the beholder may reveal it, if he/she feels confident to do so. The names of people whose death is recent are not usually pronounced either; the dead individual is referred to as “the deceased” and by his/her kinship relation with a third person.

Life cycle

A boy holds the name he has received after birth until getting another one, which happens when he is between the ages of 9 and 12. The criteria is not the exact chronological age, but the degree of knowledge he has attained. Between 3 and 5-years old, he gets a small bow and tiny arrows made by his father and starts to go along with him in fishing and hunting expeditions. He begins to learn the “talk” of the animals (that is, how the animals communicate with each other, the sounds they produce and what they indicate), the names and characteristics of the plants and trees, the local geography. By the time he is 8-10-years old, he already knows how to make his own bow and arrows, although smaller than the adults’, and uses them with some expertise. After he has mastered their use, at the age of 11-12, he has his nose pierced in the ceremony of the maize, in the rainy season, and gets his second name, an intermediate name between his child’s and his adult’s, which he will hold later in life.

He then begins to go to the men’s house during the day, where he is taught about the ceremonies, the myths and the use of medicinal plants; he also learns how to play the flute, as well as how to make feather ornaments and the bows and arrows of adults. At the same time, he assumes more systematically the responsibilities of provider of his household and village, participating increasingly more in all adult chores.

At 14-15-years old – when he is already able of killing large animals such as wild pigs, tapirs, capybaras, deer etc., and already knows enough about the ceremonies –, he used to go through the ritual of perforation of the earlobes, which occurred in the big celebration, in the dry season, that is the culmination of the annual ritual cycle. This rite, which is no longer practiced, introduced the boy into the age class of the grown-up men. He was then considered apt for marrying and also of taking part in the war expeditions the Rikbaktsa made against the Cinta-Larga, other neighboring groups and, later, against rubber gatherers. In this phase he would get his thirds name, soon after the ear perforation or after getting married.

Currently, even without perforating their ears, young men are considered adults when they reach the adequate conditions of age and knowledge. That is when they get their third name, which generally occurs after they get married. Some men may even change their names once more, when they reach maturity, head their own malocas and have grown children, a large family and social influence.

Women get their names just like men, during the ceremonies of clearing the fields, but after being subjected to different rites of passage.

Just as boys, each newborn girl gets a clan child name. In the past, around the age of 12, after having their period for the first time, the girls would have their noses perforated. Nowadays some have it and some have not. In any case, at this age they take “forest medicine” in order to reduce birth pains when, in the future, they give birth.

Traditionally, the Rikbaktsa father decided when his daughter would get her facial tattoos, which occurred during the big celebration, in the same occasion in which the boys had their earlobes perforated. After that she was considered a full woman, ready to get married.

After the nose perforation, the young woman was entitled to a new name, generally given after she was tattooed or soon after her wedding. There is no practice of reclusion of young women except during this short period of time. Neither there are menstrual huts, nor there are rules of isolation related to menstruation among the Rikbaktsa.

Today, this ritual of passage is no longer practiced, just like the perforation of the boys’ earlobes and the warring expeditions, in which the just-formed hunter had his first experience as a warrior, thus completing his preparation to be an adult, has been abandoned. The experience of being a warrior has been replaced, in recent years, by the active participation of the young Rikbaktsa in the struggle for the recovery and maintenance of their territory.

Political organization

The Rikbaktsa society is structured around reciprocity relations established among the clans that belong to the kinship Halves, which connect the individuals to the larger community. They exchange women through marriage and goods and labor in the ceremonies that one Half offers to the other in exchange for help in the clearing of planting fields. Such interdependence can be observed also in hunting, in which the hunter always gives the prey to his companion, in general a brother-in-law, who belongs to the other kinship Half.

However, in principle each domestic group forms a political unit. Traditionally there were no “chiefs”, although there have been – and there still are – leaders whose influence transcends their own households or villages. The centralized leaderships imposed on the Rikbaktsa by the missionaries were short-lived and inefficient. The most influential leaders, in addition to their personal capacity, tend to be those with the most numerous group of relatives and brothers-in-law. In recent times a new type of leader have begun to appear: young men who know well the encroaching society and who are capable of offering more adequate responses to the problems that the situation of contact imposes on the group.

In the absence of a centralized leadership, the main mechanisms of social control are gossiping, the imposition of ostracism and social avoidance.

The break in reciprocity (especially regarding family obligations derived from marriage) causes conflicts and differentiates the existing ties among the various clan subgroups. It is this relation of more or less solidarity among the Rikbaktsa that, along with economic criteria or strictly geographic factors (such as proximity to watercourses, fertile land etc.), defines the location of villages and how far the neighbors should be.

There seems to have existed, before contact, serious rivalries between the Rikbaktsa who lived on the Arinos River and those of the Sangue and Juruena rivers. The current struggle for their physical and cultural survival has strengthened the ties of internal cohesion, just as it has made possible an approximation and occasional alliances with other indigenous societies of the region.

Views about diseases, death and life

The Rikbaktsa believe there is an exchange of “souls” among beings of the physical world. Thus the fate of the dead varies according to the lives they led as human beings. Some people may come back again as human beings (or even as “whites”) or incarnated in “night” monkeys (one of the very few animals never hunted by the Rikbaktsa); others, who are believed to have been bad while alive, come back as dangerous animals, such as jaguars or poisonous snakes. On the other hand, all beings were once human, and the myths register how they were transformed into animals for good. Therefore, pigs, tapirs, macaws, birds and even the Moon were people once.

The hundreds of stories that make up the myths that gives form and sense to the lives of the Rikbaktsa are told over and over by the older Indians, and even the children use them as reference in their relations with the surrounding physical and social environment, in an effort to maintain the harmony between their activities with the immanent order of the cosmos, portrayed in their myths.

Illnesses are seen as a break in the balance resulting from taboos that have been broken (that is, acts that jeopardize the world’s immanent harmony or order) or as the product of a spell, or of poisoning by an enemy. Traditional cure methods are based on the use of plants with medicinal qualities and on ritual purifications.

All activities of hunting, gathering, fishing and planting are contained within this universe of significance, and are ritualized in the cycle of ceremonies determined by the agricultural year. The music, the chants and the feather ornaments are thus of fundamental importance, expressing in a sensitive way the Rikbaktsa’s social and mythical universe and their forms of affective, aesthetic and religious sensitivity. In the process of recovery of their ethnic dignity, the rituals, the music and the mythical narratives have crucial importance, expressing and being themselves the nucleus of cohesion and identity that enables them to face the transformations induced by contact without disintegrating as a people with an original culture and history.

There is the green maize ceremony in January, the clearing of the forest ceremony in May, and lesser ceremonies throughout the entire sequence of annual activities. The high point of the cycle takes place in mid-May, when the Halves and the clans show up with their characteristic body paintings, feather ornaments and flute songs. At that time they perform mythical stories and episodes of fights recently confronted by men of the community.

The Rikbaktsa are excellent flute players and the appropriate traditional songs are performed in each ceremony.

Note on the source

The existing bibliographical sources on the Rikbaktsa were all written after the contact established by the Jesuits. There are papers and reports written by the missionaries themselves, within the perspective of catechism and tutelage, and those by the members of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, who also had contact with the Rikbaktsa, although not as profound and as constant as the Jesuits of the Anchieta Mission. Among the works by the missionaries, the most important was written by Father João Dornstaudter, who was in charge of the “pacification” process. In it he describes the expeditions and the first contacts, as well as the regional context and the living conditions of the Rikbaktsa. Other important information sources regarding the way the Jesuits carried out their work are those written by fathers Moura and Weber.

Of the first ethnographic descriptions about the Rikbaktsa, the best are by the anthropologist Harald Schultz, who visited their area in 1962, during the first year of peaceful contact and whom, in addition to the precise text, produced excellent photographs, which he published in the two articles he wrote that deal with the Rikbaktsa.

Ethnographic descriptions can also be found in the works by Joan Boswood, of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, although her studies are more focused on the Rikbakts, as is Sheila Tremaine’s.

A more ambitious work is Robert Hahn’s, an anthropologist who worked with the Rikbaktsa in the early 1970s and produced the first dissertation about them. Directed to the analysis of the terminological kinship system, it was the first extensive ethnography about the Rikbaktsa, and studied the presence of the Jesuits and the implications of catechism over the Indians as well.

More recent works about the Rikbaktsa, so far, are mine. Firstly, the reports assessing their situation, as part of the study carried out by the Polonoroeste Project between 1983 and 1988. Among them there is the report for the identification of the indigenous areas of Japuíra and Escondido, carried out in 1985. A new report of identification of the Escondido indigenous area was made in 1993, redefining it and serving as the basis for its demarcation in 1998. Those reports give a vision of the moment, although an effort was made to rely on a perspective of the Rikbaktsa’s history.

The research funded by CNPq scholarships resulted in a report in 1988, and in my PhD dissertation in 1992. In both, I tried to present the set of historical and ethnographic information about the Rikbaktsa I was able to gather, and analyze them in the perspective of the theoretical field of Anthropology.

Later on I studied in more depth some aspects of their though in my articles "Mitos Rikbaktsa" (Rikbaktsa Myths). I also published two more articles analyzing their political and territorial struggles, and developed yet another study comparing the regional model of occupation of the space and the use of natural resources to the Rikbaktsa model, in addition to producing an ethnographic video about them.

In 1985, during the struggle for the Japuíra Indigenous Land, the police invaded the area, submitted the Indians to physical and moral pressures and arrested and tortured Father Balduíno Loebens, a missionary who had been working among the Rikbaktsa for 30 years, among other abuses. Testimonies about those facts and the lawsuit that followed them, won by the Rikbaktsa, can be found in the Dossiê Rikpaktsa, organized by the Funai indigenist Odenir Oliveira. Last but not least, there are works by the Rikbaktsa themselves, one of them written with the support of Fausto Campoli, who at the time was OPAN’s consultant on education, and another by the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Sources of information

- ARRUDA, Rinaldo Sérgio Vieira. A luta por Japuíra. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil 1095/1986. São Paulo : Cedi, 1987. p. 313-21. (Aconteceu Especial, 17).

- --------. Os direitos dos Erikbaktsa : interesses impedem demarcação da Área Indígena do Escondido. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 579-82.

- --------. Mitos Rikbaktsa : história, sociedade e natureza. Margem, São Paulo : Educ, n. 5, p. 31-58, 1996.

- --------. Relatório antropológico sobre a Área Indígena do Escondido : avaliação da situação e proposta de demarcação. s.l. : Funai, fev. 1993. 39 p.

- --------. Relatório de avaliação da Área Indígena Rikbaktsa-Japuíra e da área Indígena do Escondido. s.l. : Fipe/Minter/Sudeco, maio 1987.

- --------. Relatório de avaliação da situação Rikbaktsa. s.l. : Fipe/Minter/Sudeco, jan. de 1986.

- --------. Os Rikbaktsa : mudança e tradição. São Paulo : PUC, 1992. 543 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Rikbaktsa : retomando o Japuíra. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 453-5. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- --------; MARICONDE, Inês. Mapa de ocupação territorial : Áreas Indígenas Rikbaktsa e Japuíra e arredores. São Paulo : CTI/PUC-SP, 1994.

- BOSWOOD, Joan. Citações no Discurso Narrativo da Língua Rikbaktsa. Brasília : SIL, 1973. (Lingüística, 3).

- --------. Evidências para a inclusão do Aripaktsá no filo Macro-Jê. Brasília : SIL, 1972. (Lingüística, 1)

- --------. Phonology and morphology of Rikbaktsa and a tentative comparison with languages of the Tupi and Jê families. s.l. : SIL, 1971.

- --------. Quer falar a língua dos Canoeiros? Rikbaktsa em 26 lições. Brasília : SIL, 1978. 108 p.

- --------. Some thought on Rikbaktsa kinship. s.l. : SIL, s.d.

- CAMPOLI, F. e equipe de professores Rikbaktsa. Mypamykysonahaktsa. s.l. : s.ed., 1986. (Livro de leitura e exercícios feito coletivamente pelos professores Rikbaktsa, sob a orientação de Fausto Campoli, para uso em suas escolas)

- CHRISTINAT, Jean-Louis. Mission ethnographique chez les indiens Erigpactsa (Mato Grosso), expedition Juruena 1962. Bulletin de la Société Suisse des Américanistes, Genéve : Société Suisse des Américanistes, n 25, p. 3-37, 1963.

- DORNSTAUDER, João Evangelista. Como pacifiquei os Rikbáktsa. São Leopoldo : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1975. 192 p. (Pesquisas História, 17)

- HAHN, Robert Alfred. Missionaries and frontiersmen as agents of social change among the Rikbakca. In: HVALKOF, S.; AABY, Peter (Eds.). Is God an American? : an anthropological perspective on the missionary work of the SIL. Copenhagen : IWGIA, 1981. p. 85-107. (Document, 43). --------. Rikbakca categories of social relations : an epistemological analysis. Cambridge : Harvard University, 1976. 297 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- LUNKES, Odilo Pedro. Estudo fonológico da língua ribaktsá. Brasília : UnB, 1967. (Dissertação de Mestrado) --------. Origem, lendas e costumes dos índios Rikbaktsa. Estudos Leopoldenses, São Leopoldo : Unisinos, v. 13, n. 48, sep., 1978.

- MELLO, Alonso Silveira de. Missão do Mangabal do Juruena. São Leopoldo : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1975. (Pesquisas, História, 18)

- MOURA E SILVA, José de. Diamantino, 1728-1978 : 250 anos. Documentário. Cuiabá : UFMT, s.d. --------. Fundação da Missão de Diamantino. São Leopoldo : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1975. (Pesquisas, História, 18)

- OLIVEIRA, Odenir Pinto de (Org.). Dossiê Rikbaktsa. Brasília : Funai, 1986. 255 p.

- PACINI, Aloir. Pacificar : relações interétnicas e territorialização dos Rikbatsa. Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional, 1999. 261 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- PEREIRA, Adalberto Holanda. O pensamento mítico do Rikbaktsa. São Leopoldo : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1994. 336 p. (Pesquisas Antropologia, 50)

- PROFESSORES RIKBAKTSA. Dicionário Rikbaktsa/Português - Português/Rikbaktsa. Cuiabá : SIL, 1991.

- SCHULTZ, Harald. Indians of the Amazon darkness. National Geographic, Washington : s.ed., v. 125, n. 5, p. 736-58, 1964. --------. Informações etnográficas sobre os Erigpagtsá (Canoeiros) do Alto Juruena. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 15, p. 213-314, 1964.

- TREMAINE, Sheila (Comp.). Tsipinymyrykynahaktsa bo ky - Queremos aprender : Pré-Leitura Rikbaktsa. Cuiabá : SIL, 1993. 47 p. Circulação restrita. -------- (Comp.). Tsipinymyrykynahaktsa! ns. 1, 2, 3, 4 - Vamos estudar ns. 1, 2, 3, 4. Cuiabá : SIL, 1994. 54, 40, 33 e 34 p. (Livros de Apoio na Língua Rikbaktsa). Circulação restrita.

- ZWETSCH, Roberto E. Com as melhores intenções : trajetórias missionárias luteranas diante do desafio das comunidades indígenas - 1960-1990. São Paulo : Faculdade de Teologia Nossa Senhora da Assunção, 1993. 563 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- Os Rikbaktsa. Dir: Rinaldo S. V. Arruda et al. Vídeo cor. VHS, 10 min., 1989. Prod.: PUC-SP.