Zo'é

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- PA 350 (Iepé, 2025)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

The Indians in the Cuminapanema river call themselves Zo’é, a denomination that is still pending better understanding.

Name and language

The expression Zo'é is used only in situations of differentiating between one of "us" and the whites (Kirahi) or the enemies (Apam, Tapy’yi), the two only ethnical categories presently used by the Tupi. Except for these expressions, the Zo’é do not use other terms to define, for example, neighboring indigenous groups. In a few circumstances, they differentiate the kirahi ete, the true white, that is, the first strangers who contacted them several decades back (nut pickers and gateiros in the region), and the agents with whom they make contact now are only kiraki or kirahi amõ (other whites, not from the region). The expression poturu, initially used by Funai to designate this Tupi group, refers only to the wood the embe’po labrets are carved of: that is what the Zo’é answered when somebody pointed at them, asking for a name.

Language

The Zo’é speak a language of the Tupi-Guarani family of the Tupi branch. The entire population is monolingual, with the exception of a few youngsters who learned a few words in Portuguese hearing Funai employees talking over the radio.

History of contact

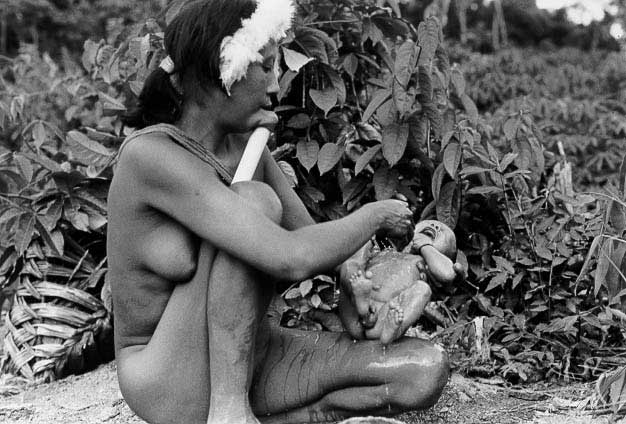

The Zo’é go down in history as one of the last intact peoples of the Amazon. Their contact with American Protestant missionaries and with Funai woodsmen was amply publicized by the media, and in 1989 the first images were shown of this Tupi people so far living in a state of isolation.

Funai was aware of the group’s existence since the early 70s at least, when the agency began the survey of isolated groups in the route of construction of the Northern Perimetral highway (BR-210). At that time, the contact with the Cuminapanema group was planned but the discontinuance of the highway works prompted Funai to desist.

By that time, there already was relatively precise information about the group’s location. By 1975, a team from Idesp (an agency belonging to the state of Pará) which was doing mapping and mineral surveys for Sudam found a clearing, which could be used as a landing strip. When they came closer, they discovered a village, with three large huts. The team decided to overfly the village, and the plane was shot with arrows. Before interrupting their works, Idesp found another three villages and communicated the "discovery" to Funai, which assigned two woodsmen to work in the region.

In 1982, evangelical missionaries of the Missão Novas Tribos do Brasil made contact with the Indians, following the overflight of four villages. According to the missionaries, this quick contact was very tense and limited to handing out a few gifts.

In the following years, from 1982 through 1985, the missionaries limited themselves to overflying the region in order to reconnoiter the location of the villages and to drop gifts. In 1985, they returned to the area and began construction of a base called Esperança (Hope), located a few days’ walk from the villages and outside the roaming area of the Indians. In two years they built a few houses and a landing strip capable of accommodating small aircraft. During this period, they made several forays towards the villages, making sporadic contact with the Indians who, according to the missionaries, remained "restless" and withdrawn.

The definitive contact with the Zo’é happened on November 5 1987, at Base Esperança: a group of Indians appeared on a hill behind the station, followed by other families until approximately 100 persons were gathered. According to the missionaries, it was a moment of great tension. Communicating through gestures, the missionaries offered gifts and were given back arrows whose tips had been broken. In the following days other Indians came and built huts on the hill, where they remained for some time.

Funai was notified of the episode. The agency then forbade the missionaries to install themselves in the villages, which prompted them to attract the Indians to close to Esperança station, where the Zo’é built huts and cleared fields. The objectives of Missão Novas Tribos were based on three stages: learning the language, to begin the literacy process and, by way of translating the bible, convey the word of the Lord to the Zo’é.

In 1989 Funai made a few reconnoitering expeditions to learn of the situation of the Indians and found out that the group’s health status was precarious at best. Relations between Funai and Missão became conflicting and in October 1991 Funai assumed control of the area, withdrew the Missão and implemented their own health care policy.

Thus, only after the last decade have the Zo’é experienced the presence of the whites, which for them stands for the introduction of high-impact technologies and their subsequent attraction towards Funai stations, installed in their territory as because of the white man’s interests and the resulting outbreak of new diseases which entail greater population concentration around the stations. In many aspects, this people’s situations shows many similarities with other 50 isolated Amazonean groups. There are, however, some peculiar characteristics which deserve mention:

- even though they’ve established permanent coexistence relations with the station on their own initiative, the Zo’é had already experienced occasional contacts with nut pickers and pelt hunters at least 50 years back;

- their settlement in a secluded area between the Cuminapanema and Erepecuru rivers indicates that they’ve attempted to keep their distance both from neighboring indigenous peoples, whom they treat as enemies, and from the whites for decades;

- contrarily to other intermittent contact experiences, it was during the recent contact process (1982/90) that they suffered their most dramatic demographic casualties, resulting from the dissemination of previously unknown diseases, ensuing a growing contamination process;

- due to the difficult access conditions and the non-existence of state or federal development programs for the Northern area of the state of Pará, the area is still relatively preserved; however, small prospecting groups installed along the banks of the rivers delimiting the area: Erepecuru (where several land strips were cleared) and Curuá. To this moment, the Cuminapanema/Urukuriana Indigenous Area is only "interdicted." This is a precarious legal situation: "identification" of the land began in 1997, rolling out the long land recognition process which will assure the Zo’é the exclusivity in the occupation and exploration of their lands.

It is a fact that the Zo’é are out of their isolation. The transition to permanent coexistence with contact agents is manifest in the dependence process in which they are and the restructuring of their pace of life and their territorial occupation as a function of the presence of care agents. Cuminapanema visibly shows all the elements of a process which historically follows the implementation of a "protection"- oriented care policy.

Now, the main peculiarity of the contact relations in course in the Cuminapanema is related to the fact that assistance agencies came forward in the intensive coexistence of Indians with the regional occupation. MNTB, and later Funai promoted interventions whose declared purpose was to guarantee and preserve the "isolation" of this ethnicity. A unilateral decision, contrasting with the Zo’é’s decision to have access to the outer world, according to their own pace and terms. Since they’ve opted for permanent coexistence relations with the whites in 1987, the Zo’é have manifested a growing curiosity in unraveling the world around them: they wish to maintain more intense contact with the whites, they want more objects, they want to visit the white man’s city, and they want to meet other Indians."

Ways of life

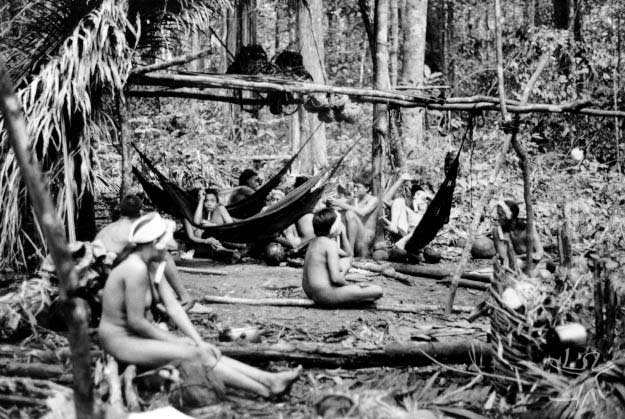

As the other peoples in the Guyanas region, the Zo’é have a decentralized social structure, highlighted by the political and economic autonomy of the local group. More than a local group may populate the same village. Each hut houses one core family or two units which occupy separate spaces in the hut, each one having its own hearth.

Their economic activities are split into two movements: a relatively sedentary positioning as a function of their agricultural practices and an important mobility entailed by their hunting and fishing activities.

Because of the stone-age technology deployed by the Zo’é until not very long ago, the fields are reused every year, and cassava and other products are replanted in the same clearings. For this reason, there are few fields and therefore few villages in the area. Contrarily to this sedentary pattern, hunting and fishing activities drive the families to places far away from their villages, where they remain for several weeks enjoying the abundance of game and complementing their diet with flour prepared at the village. This alternation of activities oriented towards agriculture and flour-making with long-range expeditions translate into a great mobility in the area.

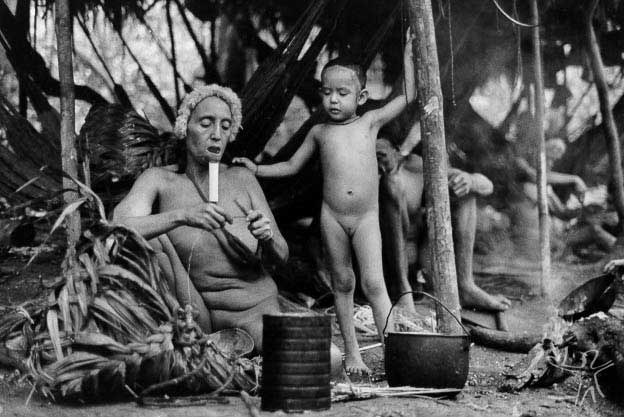

The material equipment used by the Zo’é in their subsistence activities comprises a limited number of artifacts among which ceramics and woven items prepared by women and designed for the processing of cassava.

Location and population

The Zo’é inhabit a strip of land crossed by small igarapés and tributaries of two large rivers, the Cuminapanema and the Erepecuru, in the municipality of Oriximiná, Northern Pará. It is a mountainous region with large Brazilian nut trees, which boasts the maximization of subsistence resources. Besides cassava, which corresponds to approximately 90% of the planted fields, the Brazilian nut is the most-consumed product by the Indians, who also use its husk and skin to make many of their artifacts. The territory occupied by the Indians is crossed by small igarapés, where they fish using the timbó weed. The relative scarcity of fauna resources in this occupation zone results from the long time of village existence and, therefore, a depletion of game. The area inhabited by the Indians corresponds to a secluded area where the Zo’é kept isolated from the whites, whom they knew by way of intermittent contact for several decades, and other neighboring indigenous peoples, whom they regard as enemies.

The Zo’é accepted the pacific coexistence with the whites in 1987. Four years later, an estimated 45 individuals died from malaria and influenza epidemics. In 1991 they numbered 133 individuals. Today, amidst a demographic recovery process, their population numbers more than 150 persons.

Sources of information

- BINDA, Nadja Havt. Representações do ambiente e territorialidade entre os Zo'é/PA. São Paulo : USP, 2001. 209 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CABRAL, A. S. A. C. Algumas evidências lingüísticas de parentesco genético do Jo'é com as línguas Tupi-Guarani. Rev. Cursos de Pós-Graduação em Letras, Belém : UFPA, v. 4, 1996.

- --------. Notas sobre a fonologia do Jo'é - Moara : estudos de línguas indígenas. Rev. Cursos de Pós-Graduação em Letras, Belém : UFPA, v. 4, 1996.

- GALLOIS, Dominique Tilkin. De arredio a isolado : perspectivas de autonomia para os povos indígenas isolados. In: GRUPIONI, Luís Donisete Benzi (Org.). Índios no Brasil. São Paulo : Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, 1992. p. 121-34.

- --------. Essa incansável tradução : entrevista. Sexta Feira: Antropologia, Artes e Humanidades, São Paulo : Pletora, n. 6, p. 103-21, 2001.

- --------. Tupi do Cuminapanema : eles se chamam Zo'É. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 280-7.

- --------; CARELLI, Vincent. Diálogo entre povos indígenas : a experiência de dois encontros mediados pelo vídeo. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 38, n. 1, p. 205-59, 1995.

- GALLOIS, Dominique Tilkin; GRUPIONI, Luís Donisete Benzi. O índio na Missão Novas Tribos. In: WRIGHT, Robin (Org.). Transformando os Deuses : os múltiplos sentidos da conversão entre os povos indígenas no Brasil. Campinas : Unicamp, 1999. p. 77-130.

- --------. A redescoberta dos amáveis selvagens. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 209-14. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- GALLOIS, Dominique Tilkin; HAVT, Nadja. Relatório de identificação da Terra Indígena Zo'é : Portaria 309/PRES/Funai - 04.04.97. São Paulo : Funai, 1998.

- HAVT, Nadja. De algumas questões sobre a participação de “índios isolados” no processo de regularização fundiária : o exemplo dos Zo’É. In: GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Org.). Demarcando terras indígenas II : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 2002. p. 85-94.

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall'Igna. Línguas brasileiras : para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas. São Paulo : Loyola, 1986. 135 p.

- --------. Relações internas na família lingüística Tupi-Guarani. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 27/28, p. 33-54, 1984/1985.

- SILVEIRA, Maria Luiza dos Santos. Identidade em mulheres índias : um processo sobre processos de transformação. São Paulo : USP-IP, 2001. 377 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- THOMAZ, Omar Ribeiro. A periferia de São Paulo descobre os índios Tupi do Cuminapanema. Tempo e Presença, Rio de Janeiro : Cedi, v. 14, n. 262, p. 38-41, mar./abr. 1992.

- A arca de Zo'É. Dir.: Dominique T. Gallois; Vincent Carelli. Vídeo Cor, VHS, 22 min., 1993. Prod.: CTI-SP